By Marcy Stamper

Photography by Roxanne Best

In all her art – whether it’s mixed-media, photography, film, sculpture, or printmaking – Dr. Michelle Jack reimagines and repurposes tools and materials, as her syilx people have done for centuries.

Dr. Jack, a member of the syilx/Northern Okanagan/Penticton Indian Band who describes herself as an abstract image maker/scholar, draws on this wide range of art forms to tell the essential stories of her people and the land.

Traditionally a nomadic people who moved with the seasons, the syilx – their families, land, and access to traditional foods – are now separated by the United States/Canada border. Dr. Jack lives and works on both sides of that border, in Omak (nisɬpícaʔ) and Penticton (snpintktn), British Columbia.

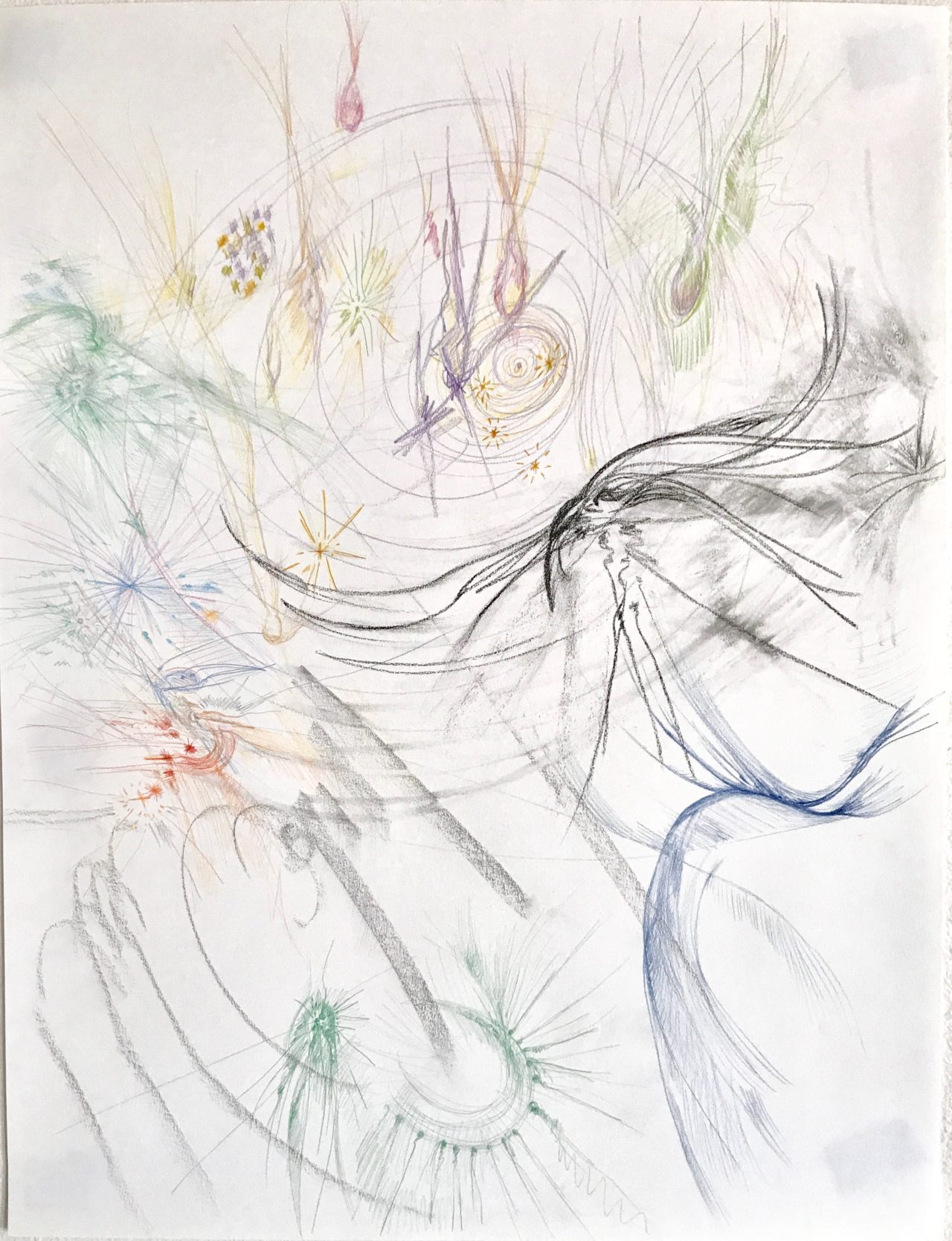

While Dr. Jack’s art making is diverse, some elements, including layering and references to the land, are a key component of much of her work. Many pieces have an elegant, translucent effect, with the layers adding complexities of texture and depth. Dr. Jack’s color palette recalls the Okanogan landscape.

In her mixed-media piece “kɬ cpəlk̓ stim̓” (“To Cause to Come Back”), Dr. Jack gives voice to the land istself. In colors that celebrate the water, earth, and mountains, Dr. Jack depicts the return of the salmon chiefs and the sun, as it breathes life back into rivers.

“It’s helping re-envision how the land is speaking back, and what the land wants to happen,” she said. “We have to listen to the land to know what it wants us to do – not from any Western culture, but what our ancestors and the land are asking us to help with.”

In “Flight,” Dr. Jack used delicate tracings of lines, curves, and other geometric forms to suggest movement and exploration.

tracings of lines, curves, and other geometric forms to suggest movement and exploration.)

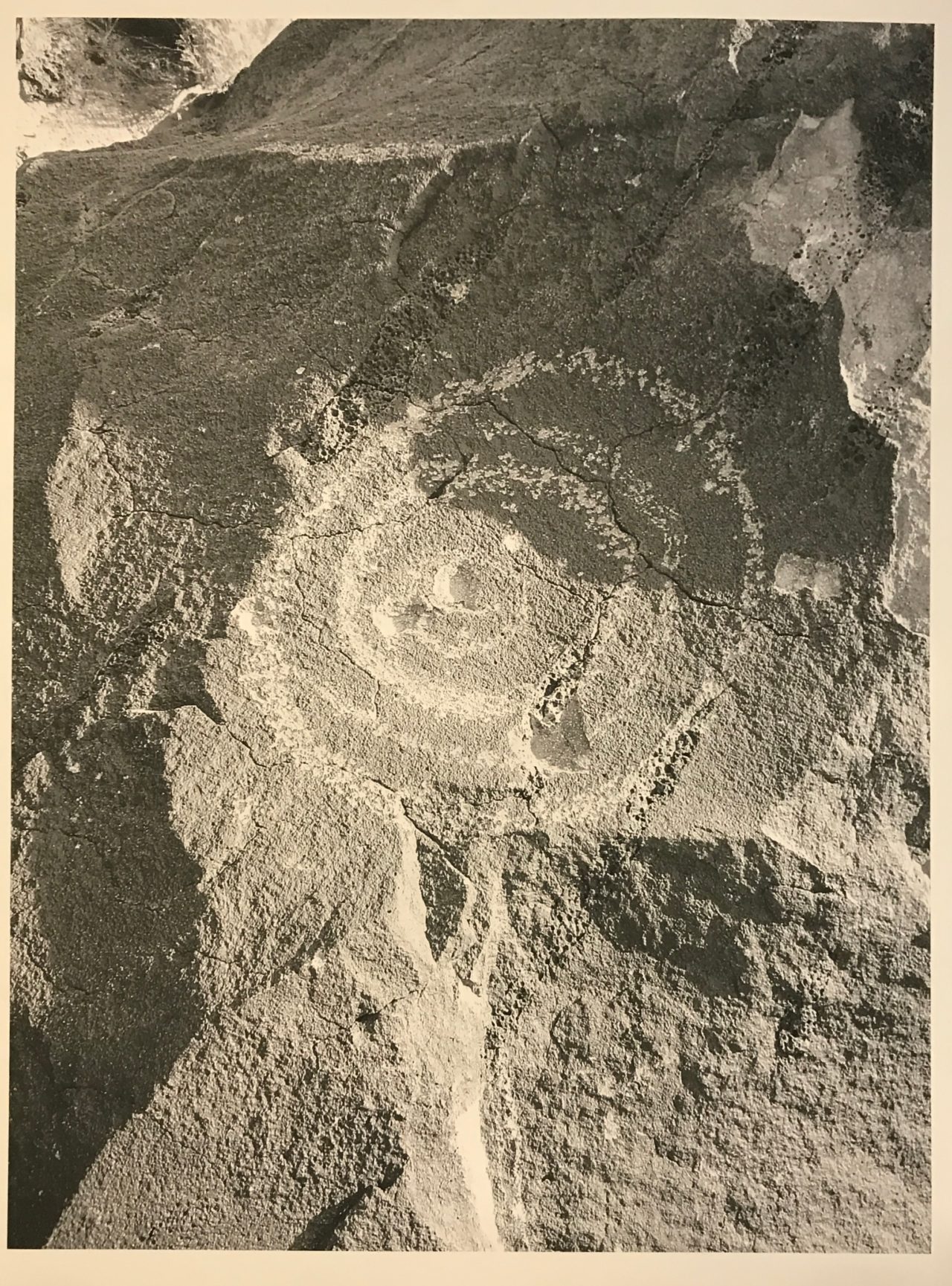

Dr. Jack’s photographs often include the most elemental aspects of the land, the stones, plants, and sky. But in one panoramic image, she examines what has happened to that land – small shrubs dot a fractured landscape of highways, concrete retaining walls, and cars.

The translucent layers that characterize much of Dr. Jack’s work allow her to superimpose images and to depict their flow, back and forth, between times and continuums, she said.

“My main thing is that I always try to honor the traditional teachings and knowledge that my grandparents and ancestors have shown us. I strive to carry myself with the most respect and honor for those traditions, and that comes out in my work,” she said.

Ingenuity and adaptation are central themes in Dr. Jack’s art. This adaptation is a traditional practice among the syilx, who have a long history of reusing things, she said.

Dr. Jack takes that tradition a step further. She’s interested both in using modern tools in a traditional way and in finding new uses for traditional implements. “I’ve always used tools and things in a different way from how they’re intended,” she said. “It’s a traditional tenet that my people are known for.”

“Just because something has a certain purpose, we can still repurpose and use it how we want it,” she said. “That’s a very traditional idea, but it’s a new twist to incorporate contemporary and native materials.”

Even paints, pigments derived from the land, and shellac get that treatment in Dr. Jack’s art. While shellac is typically applied as a protective layer, it causes subtle deterioration of the paper. To Dr. Jack, that becomes an opportunity for exploring what happens as the materials transform.

Lifelong practice

Dr. Jack has been making art as long as she can remember. Even early on, her art has been a vehicle for exploring the many worlds she inhabits.

By age 14, Dr. Jack had a subscription to ARTnews. She also read Native American Art magazine to learn about Indigenous artists.

In the 1980s and ’90s, ARTnews featured, almost exclusively, white artists who created abstract art. They may have been experimenting with line, form, and color and challenging customary subject matter, but they didn’t upend the cultural context in which that art was created, Dr. Jack said.

Still, in ARTnews, Dr. Jack discovered abstract expressionists and color-field painters whom she admired for the way they presented their own perspective on the world and didn’t filter it through standard cultural expectations.

Their way of expressing the world around them, through layering and texture, resonated with Dr. Jack from an early age. She knew that the western European approach to art didn’t reflect her culture or the land and water. “It was really helpful to read about how these artists circumvented all those constructs,” she said.

So it was a natural outgrowth that many of Dr. Jack’s projects expose the historical inaccuracies and misappropriation that have long characterized depictions of Indigenous people.

In her “Border Trials” exhibit, Dr. Jack revisited the photographs of 19th- and 20th-century photographer Edward Curtis from a contemporary perspective, skewering the familiar representations with pungent humor.

Curtis has long been celebrated for his portraits, which purported to show Natives in their traditional dress. But Curtis took significant liberties, combining clothing and regalia from different cultures that didn’t belong together – purely for visual effect, Dr. Jack said.

So, Dr. Jack produced her own portrait series. She mimicked Curtis’ style, using the same historical technique for processing the film. But she put herself in front of the camera, posing as an Indian princess in unlikely garb. In one image, she wore a headdress with two feathers that resembled Playboy Bunny ears, to show how mainstream culture has objectified women and Indigenous people.

In another image, Dr. Jack wore a dress she fashioned out of brown paper bags and black gaffer’s tape. But because Dr. Jack used the same photographic process Curtis employed, in her lush, sepia-toned images, her paper dress looks like a garment with deep cultural meaning. “It showed how Curtis falsified things and didn’t accurately represent people,” Dr. Jack said.

Dr. Jack also upended the context in which museums have tended to interpret Indigenous people and cultures when they exhibit their art in artifact cases, as an anthropological curiosity rather than art.

Dr. Jack’s lifelong connection to the land inspired a project on climate change back in 1991. Dr. Jack’s awareness of the changing climate was nurtured by her grandmother, who taught her how to watch the weather. When you live on the land, it’s crucial to be aware of how the weather is shifting, Dr. Jack said.

Cyclical change

Dr. Jack’s fluency in many mediums allows her to choose the approach that will best express a particular idea. Dr. Jack still uses photographic film to create multiple exposures and to layer using light. To add each new layer, she has to imagine the composition in her mind’s eye to achieve the desired overlap.

Cameras – Dr. Jack even uses an inexpensive novelty camera from the 1990s – turn out to be an ideal medium for her message. “We are peoples of continuous cyclical change. The modern tool, the camera, walks with us on this border,” Dr. Jack said in her artist’s statement for an Indigenous artists’ residency at the University of British Columbia in 2019.

Not only is Dr. Jack interested in blending art and cultures but she also sees a commonality in disciplines usually treated separately in academia. Dr. Jack always loved math and science, and even taught math for several years. “Theoretical math is really similar to art,” she said. “They both involve the hypothetical contemplation of what could be. They’re both about creative thinking.”

Dr. Jack has also used her art to build awareness of artificially imposed land boundaries. Her family lives on both sides of the United States–Canada border. Other relatives are in the southwest, where they encounter a different set of border dynamics.

While people typically think of this country’s southern boundary with Mexico as the primary border issue, the northern border – and the way it’s administered – has a huge impact on people’s lives, Dr. Jack said. People can’t easily travel across the border to visit family or to access their traditional foods. “It’s impacting people’s communities, individual families, traditional food gathering,” she said.

In addition to being a practicing artist, Dr. Jack is a professor of visual and creative arts at En’owkin Centre in Penticton. With her students on the other side of the border, Dr. Jack has been teaching remotely since the start of the COVID pandemic. While that has added a level of complication, it’s proven less daunting than she’d expected, she said. It’s just another example of adaptation. “We have a tradition of readapting and repurposing things – that’s the thing we always do,” she said.

Dr. Jack lives and chronicles that change and adaptation. She has watched as the art world – and the business of art – have evolved. Although even in the early 2000s, there was little space in galleries for young, Indigenous artists to exhibit their work, that has started to shift, she said.

Still, Dr. Jack remains discouraged that large galleries and prominent museums still want to control the narrative when presenting work by Indigenous artists. “There’s still tons of work to be done to provide opportunities,” she said.

For Dr. Jack, the processes of making art, sharing ideas through exhibitions, and the commercial market are distinct, each with its own role.

Her art practice isn’t just about selling art, but part of a deeper relationship with viewers and collectors, she said. An art collector is a caretaker, and that requires a certain outlook and respect, she said. In fact, Dr. Dr. Jack doesn’t sell her most personal pieces.

“So, I do separate work for commercial gallery sales because I have a responsibility to my ancestors, the land, the culture I come from, the language [nsyilxcən (interior Salish, northern Okanogan dialect)],” she said. With her highly attuned sense of place, she said, “I can’t have my art go without thought of where the pieces are going to be.”

Dr. Jack appreciates that teaching leaves her free to create art that communicates her interests and to explore complex ideas unflinchingly. “I do my artwork because that’s one of my purposes for being on earth,” she said.