CLICK HERE to download PDF of the Fall ’18 ART Magazine

Article by Marcy Stamper. Photographs by Stephen Mitchell.

It was decades ago, but oil painter Michael Caldwell still has a vivid memory of his experience of seeing a painting by Henri Matisse. Looking at other art in the gallery, Caldwell was drawn to Matisse’s painting by a growing awareness of the color red, which seemed to fill the space near him.

Matisse’s painting, called “The Dessert: Harmony in Red,” had a red background and a red table, where a woman with bright yellow hair, wearing a black dress with a white collar, is serving a tray of dessert. A funky little tree was visible through the window, said Caldwell.

“The red came out of the painting and surrounded you. It was like a magical experience – that had never happened to me before,” said Caldwell.

Caldwell was an art professor for more than 30 years, and his excitement for conveying the power of art is still palpable. But Caldwell doesn’t insist on a singular version of what makes art meaningful. “We’re all attracted to works of art because we like the way something looks. It’s an individual experience based on who you are,” not that different from what attracts you to another person, said Caldwell. “But then I start taking it apart.”

Caldwell recalls a portrait by the 16th-century Venetian master Titian in a museum in London. He ended up going back seven days in a row to study the painting. “Each time, it revealed something else – the way he used color and composition,” said Caldwell.

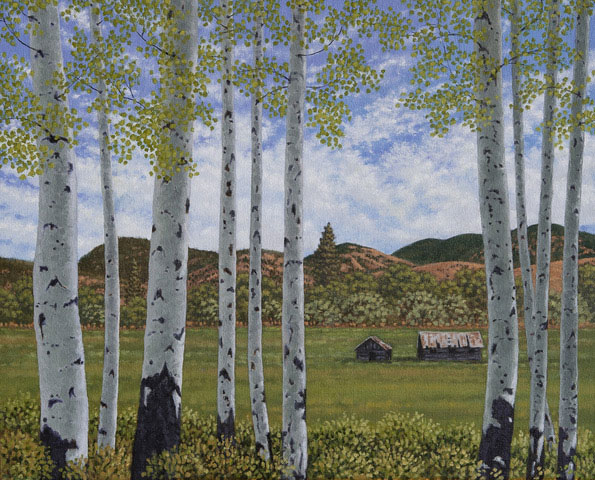

(Idaho Ranch – oil on D. Smith Art Board – 9×22.)

Another memory also hinges on his experience of color. He was visiting an Italian cathedral covered with panels depicting the life of Christ by the 13th-century painter Giotto. “The sky outside was that intense Italian blue,” said Caldwell.

Another memory also hinges on his experience of color. He was visiting an Italian cathedral covered with panels depicting the life of Christ by the 13th-century painter Giotto. “The sky outside was that intense Italian blue,” said Caldwell.

The cathedral’s vaulted ceiling was painted blue and speckled with little stars. “I swear, that blue was more intense than the blue outside. It took you from the physical world to the spiritual world,” he said. It wasn’t a religious experience, but about the art, which was accessible to anyone, regardless of faith, he said.

Caldwell draws on these experiences when he paints, thinking deeply about how art creates a visceral response in both the artist and the viewer.

Although Caldwell bases all his paintings on photographs, he always alters the scene in some way. He takes overlapping snapshots to create an old-fashioned panorama of a landscape, then tapes them together to create a complete view.

“I invent things for them – it’s not a replication of a place,” he said. “But I like the idea that you could go there.”

Unlike artists who expect ideas to emerge as they work, Caldwell decides what he’s going to change from his photograph before he starts painting. “I think about how quickly the eye will move,” he said.

Caldwell is deliberate about finding a device that will invite the viewer into a painting. He pointed to a painting where a small creek flows across a field towards low hills in the distance. “The idea was that you can move into the space through changes of colors in the field, or that your eye is drawn to the creek,” he said.

Caldwell’s paintings are usually about space – fields or meadows, with mountains in the distance, a few well-placed clumps of trees, and sky – a vast expanse of sky. Buildings, maybe a house or a barn, are usually dwarfed by the landscape.

Caldwell’s paintings are usually about space – fields or meadows, with mountains in the distance, a few well-placed clumps of trees, and sky – a vast expanse of sky. Buildings, maybe a house or a barn, are usually dwarfed by the landscape.

Caldwell carefully creates openings in trees to give the viewer a passage. “The configuration of trees is a square or rectangle with open space around them – that’s the way I look at things,” he said.

Although Caldwell’s landscapes are extremely detailed, occasionally verging on photo-realism, he is very influenced by abstract color-field paintings. He likes to intensify colors from nature and always includes subtle variations of color in the sky.

Caldwell pointed to one painting, where a deep blue sky, punctuated by feathery clouds, fills the majority of the canvas. “I like to lay wispy clouds to organize it, so it leads the eye in and then back over your head,” he said, showing how the clouds guide the viewer’s gaze upwards from a clump of aspens at the edge of the canvas.

“The eye is forced to go through the hills or little windows in the trees,” he said. “I like the horizontal plane of the ground, with distant hills where trees pop up.”

Although Caldwell takes regular trips to take photos – sometimes returning to a scene many times – he doesn’t intentionally go looking for inspiration. “But I’m always looking for something. It could be the light, the configuration of forms, or the sense of space or colors,” he said.

Although Caldwell takes regular trips to take photos – sometimes returning to a scene many times – he doesn’t intentionally go looking for inspiration. “But I’m always looking for something. It could be the light, the configuration of forms, or the sense of space or colors,” he said.

Caldwell paints some scenes right away, but others sit for many years until he figures out the approach he wants to take.

Caldwell is drawn to the landscapes of Wyoming and Montana, with their expansive vistas and small creeks etched into the ground. “I’m always attracted to subject matter with big skies,” he said.

Caldwell is drawn to the landscapes of Wyoming and Montana, with their expansive vistas and small creeks etched into the ground. “I’m always attracted to subject matter with big skies,” he said.

Although he likes to paint birds or animals – usually livestock like horses or sheep – these days, Caldwell’s paintings never include people. Caldwell got his fill of portraits in graduate school, when he made life-size, standing figures rendered painstakingly in pencil.

“It was very labor-intensive and systematic. I would lay out the figure on paper using a slide so that there were no erasure marks,” he said.

Then Caldwell began filling in the details in pencil. Drafting pencils come in gradations of hardness, with nine levels of hardness, each one able to make a slightly darker mark, and nine levels of softness, plus one pencil in the middle. For the portraits, Caldwell started with the hardest lead and colored in all the lightest areas, then moved through each subtle change in tone until he was applying dark graphite marks. “It would take forever,” he said.

While his current paintings are very representational, Caldwell has done many abstract works over the years. After the life-sized pencil portraits, Caldwell did a series that featured a dark field of color punctuated by a rectangle that suggested a door or window. In some, a wavy line hints at a hill or other landform visible through the opening.

While his current paintings are very representational, Caldwell has done many abstract works over the years. After the life-sized pencil portraits, Caldwell did a series that featured a dark field of color punctuated by a rectangle that suggested a door or window. In some, a wavy line hints at a hill or other landform visible through the opening.

Caldwell also painted a series of abstract works based on sketchbooks he kept during a trip to Europe. The paintings are intensely colored, with layered rectangles and center lines that recall the pages of his sketchbook. The shapes reminded him of doors and windows, so he added strokes to represent distant mountains or a bank of clouds.

When Caldwell returned to painting landscapes, he retained that same attention to detail and the meticulous system of making paintings. He starts with the sky on the upper left and works across the canvas. He blends colors for the sky and uses tiny dabs of paint for the mountains, trees, and water.

“I still think about the paintings in the way I thought about abstract pieces,” he said. “It’s about layers – I see various surfaces. It’s a very abstract-expressionist idea.”

As a kid, Caldwell drew all the time. “I always wanted to teach,” he said. “The first day I walked into kindergarten, I was in love with school.”

Caldwell planned to study English literature in college so he could become a teacher. Soon his attraction to the visual world won out and he thought he’d pursue geography and make maps. Then, at the last minute, he got in line for the art department.

Caldwell planned to study English literature in college so he could become a teacher. Soon his attraction to the visual world won out and he thought he’d pursue geography and make maps. Then, at the last minute, he got in line for the art department.

Caldwell retired in 2006 after a long career as a professor at Seattle Pacific University, where he taught drawing, painting, and art history. During his teaching career, Caldwell always did his own painting and exhibited widely in galleries in Seattle and beyond. He also curated the school’s gallery, building a reputation for exhibiting work by emerging artists.

Today he is committed to his oil painting and to refining his approach to his favorite subjects. He starts with a clear vision and works on one painting at a time, focusing on what the painting needs and how to invite the viewer into it. “I just finished this one,” he said, before quickly correcting himself. “I brought it to a stopping point – paintings are never finished.”

“I think that’s the magic part of art. It has the capacity to make you see, and to transform you,” he said.

CLICK HERE to download PDF of the Fall ’18 ART Magazine

Photographs were taken by Stephen Mitchell.