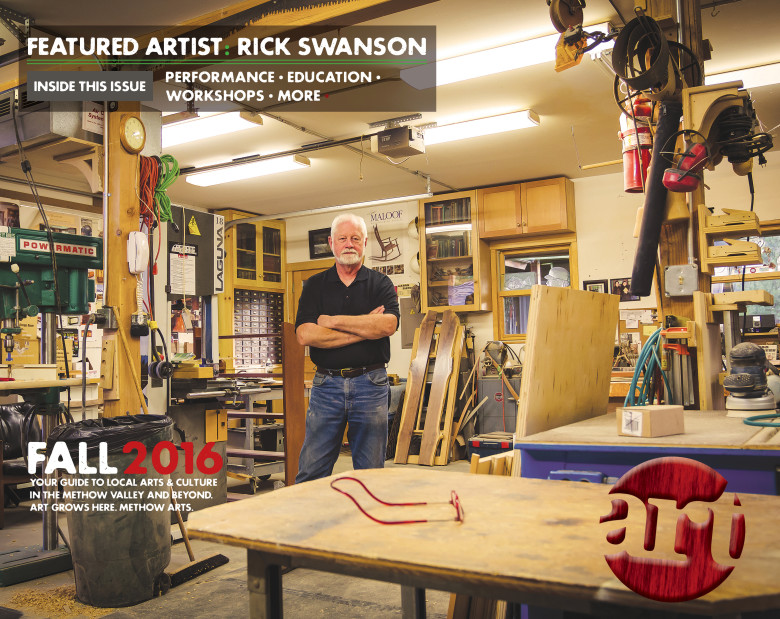

Rick Swanson’s Woodcraft

CLICK HERE TO VIEW PDF OF FALL ’16 FEATURE

By Marcy Stamper

Photography by Mandi J. Donohue

Rick Swanson’s woodworking has come a long way since his first project, a rudimentary cage he made four decades ago for pet lab rats he inherited from a friend. He was so frustrated by his flimsy wood-frame-and-chicken-wire construction that he smashed the thing into pieces with a hatchet.

Despite that inauspicious start, Swanson proved to have a natural facility for how things fit together. Today, he builds sumptuous cabinetry and furniture, executing the designs almost instinctively.

“With a piece of wood in my hand, I design a lot better—designing in my head,” he said. “I pick up the wood and I design as I cut, following the pattern of the grain. It’s more fun and spontaneous.”

“With a piece of wood in my hand, I design a lot better—designing in my head,” he said. “I pick up the wood and I design as I cut, following the pattern of the grain. It’s more fun and spontaneous.”

Although Swanson has a background as a draftsman, he was essentially self-taught when he began working with wood. He still draws formal plans on paper to plot dimensions, but the creative part of his designs—selecting the wood and figuring out how he will enhance the pattern of the grain—tends to evolve as he works. Swanson studied architectural and industrial drafting but, by the time he got his degree, he learned he didn’t want to spend his days leaning over a drafting table.

(Kitchen cabinetry in beech. Photo, Mary Kiesau, Mountain Kind Photography.)

Swanson grew up in a working-class family. His parents had lived through the Depression and couldn’t imagine anyone pursuing a career as an artist or artisan. “My parents were totally stunned and confused when I told them I would be a furniture maker,” he said.

Not that Swanson’s father—who spent his leisure time on remodeling projects—didn’t fantasize about working with wood. “He thought it was amazing that, what he liked to do on weekends, I do for a living,” said Swanson.

Helping his father finish their basement gave Swanson early exposure to wood projects, but his hands-on involvement was restricted to holding plywood while his father cut it.

Swanson looks forward to using the collection of precious woods he has amassed over the past 35 years. He pointed to a rare Oregon fiddleback walnut that he calls a “once-in-a-lifetime tree.” He built his dining room table from the wood, but has enough left for other projects. “I’d rather have wood and tools than money,” he said.

As a young adult, Swanson paid his own dues. One of his first jobs was working in a factory making artificial vanilla. Perhaps ironically, the job had a tenuous connection to wood—vanillin is made by cooking wood pulp in a potent solvent.

After four years working alternating shifts at the vanillin factory—one week on day shift, the next on graveyard, and then on swing shift—Swanson quit to produce furniture for a friend who owned an antiques store.

His friend had built a successful market for refinished oak furniture that had originally been sold mail-order through Sears, Roebuck catalogues. “The pieces looked simple enough,” said Swanson. “I thought I could make furniture like that.”

Swanson started out with simple projects, building medicine cabinets, plant stands, and spice racks that he sold through his friend’s shop. When he wanted to learn a new technique, he would design something more complicated and then figure out how to make it.

Soon Swanson got a booth at a street fair. By the end of his first weekend at the fair, he had orders for 30 jewelry boxes, plus commissions for bookcases and coffee tables.

Accustomed to figuring things out on his own, Swanson made multiples of each new design until he’d perfected it, and then upped the ante by devising a more challenging design.

He ultimately enrolled in a program in cabinetry to get more solid skills. The instructors encouraged him to continue designing and building his own furniture but helped him learn about tools and construction techniques.

In his approach to woodworking, Swanson still embraces the values he grew up with. “I wanted to build furniture for people like myself—reasonably priced, functional. My original idea was to create very affordable furniture for everyman,” he said.

That philosophy comes through in his aesthetic, which is influenced by the clean lines and unembellished forms of Danish and Asian furniture and of the American Arts and Crafts movement. “Function is the first place I go,” he said.

The distinctiveness of Swanson’s work comes from how he uses geometry to accent the inherent beauty of the wood, paired with details like drawer handles and joinery in varying tones and textures.

A sideboard Swanson built for a gallery exhibit is a showpiece of his skill and style. Swanson meticulously matched the grain of several exotic woods for the piece, which has gently angled sides and contrasting tones and patterns. “It was kind of an epiphany—if I didn’t think about it too much, I wouldn’t screw it up,” he said.

Swanson spent the first 10 years of his woodworking career designing and building furniture. It wasn’t until he decided to redo his own kitchen in Seattle that his business expanded to include cabinetry.

“It was pretty intimidating to build something that would fit in someone’s house,” he said. But after people saw the cabinets he built for his own kitchen, they started asking him to do their kitchens, too. Now Swanson sometimes ends up creating an entire interior environment.

Swanson perfected a technique for building the basic boxes for cabinets out of plywood so that he could manage them on his own in his small basement studio in Seattle. “After all, a kitchen’s just a bunch of boxes with nice faces on them,” he said.

While the basic form may essentially be a box, Swanson’s cabinets are furniture-quality and have custom features like storage for wine bottles or drawers that penetrate the depth of a wall.

It’s especially gratifying to work with clients throughout a project, said Swanson. “That’s the neat factor,” he said. “I try to involve people in the process. People like to see their project evolve.”

“It’s fun—it’s important to me,” said Swanson, who admitted to lingering insecurity even after 43 years. “I’m afraid I will get done and people will say, ‘That’s not what I thought I was getting.’” In fact, the usual response is, “That’s a lot nicer than I thought it would be.”

Because woodworking can be somewhat solitary, Swanson has always found ways of connecting with other artisans.

In the early years of his career in Seattle, he helped form a woodworkers’ guild, where members shared information and skills and sponsored workshops. A few years later, he helped start the cooperative Northwest Gallery of Fine Woodworking in Seattle (now called the Northwest Woodworkers Gallery).

A particularly influential phase of Swanson’s career was being part of a unique collaboration working on a five-acre estate on Mercer Island that was an expression of the owners’ artistic vision. Swanson was one of dozens of artists and artisans who worked on the property—he spent about a year doing the woodwork for the Japanese-influenced shower and sauna house. “It was an odd but wonderful and stimulating place to work,” he said.

Swanson moved to the Methow Valley 10 years ago, but his connections with the area and its arts scene go further back. He and his wife, Katie, were part owners of the Confluence Building for about five years, and they ultimately helped the gallery obtain the financing to purchase the building.

After years of working primarily on commission, Swanson is interested in focusing more on original pieces for art exhibits. “Being in a show can push my limits,” he said. He’s currently working on a series of tables that incorporate geometrically intricate floor-ventilation grates and glass tops. He has also been using live-edge pieces of wood to frame mirrors.

He often tries to create something he’ll be able to use if a piece doesn’t sell. For an exhibit several years ago, Swanson designed a bed with a headboard depicting the headwaters of the Twisp River. Each layer of wood—he used seven different types, including narra, wenge, mahogany, and bird’s-eye maple—is slightly thicker than the others to give the landscape added dimension.

“I told Katie that if it didn’t sell by the time she turned 60, it was hers,” said Swanson. They lucked out—Swanson didn’t get an order for a bed until two months after Katie’s birthday.

Along with the intricate headboard, Swanson incorporated practical features, such as a set of drawers beneath the mattress. “I figure rather than collecting dust bunnies, why not use the space?” he said.

Swanson looks forward to using the collection of precious woods he has amassed over the past 35 years. He pointed to a rare Oregon fiddleback walnut that he calls a “once-in-a-lifetime tree.” He built his dining room table from the wood, but has enough left for other projects. “I’d rather have wood and tools than money,” he said.

Swanson is also interested in sharing his knowledge of woodworking—and the philosophy he brings to it. “I have such a broad background, and no one to pass it on to,” he said. “I’d show how things are made. It’s helpful to understand how things are done—it’s helpful in all kinds of decisions in life.”

Although Swanson has always dedicated long hours and passion to his craft, he feels awkward being introduced as a master woodworker. “If I’ve mastered it, I’d have to stop and do something else,” he said.

In addition to the rare wood, Swanson has a collection of tools he wants to use, including a lathe and carving tools he inherited from his father and Katie’s grandfather. “I need to retire so I can play with wood,” he said.

“There’s so much you can do with wood—it’s unlimited, really.”

—————————-

Learn more about Rick and view photos of his works on his website www.swansonwoodcraft.com

View photographer Mandi J. Donohue’s website HERE