CLICK HERE to download PDF of the Winter 2018-19 ART Magazine

Article by Marcy Stamper. Photographs by Sol Gutierrez.

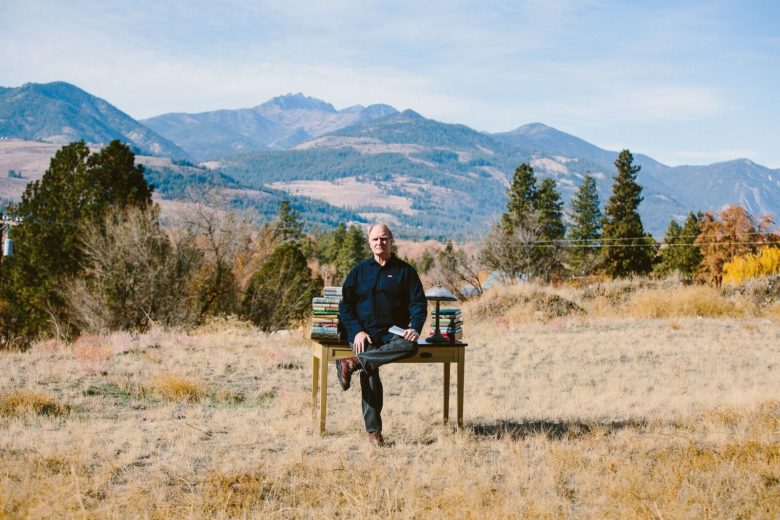

Peter Donahue writes about ordinary people – as he puts it, “people who have to live their lives under the pressure of big, historic forces.” His characters – aspiring actors, old Merchant Marines, junkies – often struggle against these forces as they come to terms with their lives.

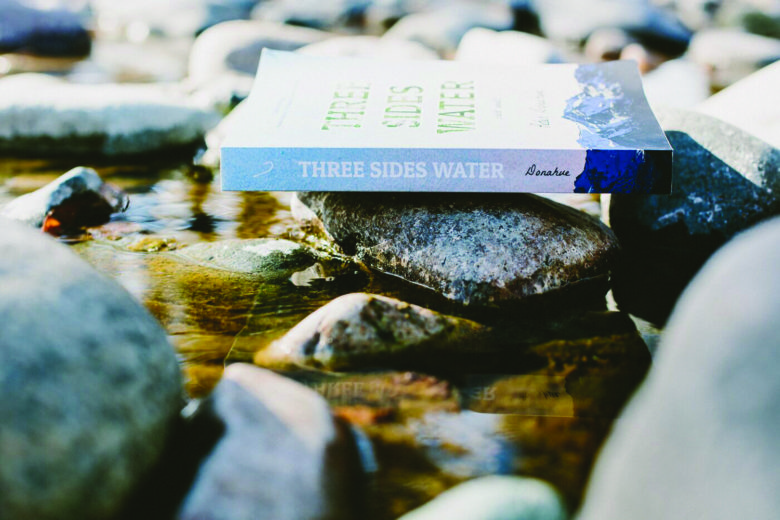

But there’s nothing ordinary about Donahue’s prose. In his most recent book, Three Sides Water, Donahue writes about “a short fellow with stocky arms and legs and a chest like a pickle barrel that stretched his red suspenders. He had a dirty gray beard that looked like a tuft of tree lichen and wore a brown felt hat with a brim that extended out to his shoulders.” Not only does the language capture the character, but it also evokes the story’s moody setting on the Olympic Peninsula.

In an era where genre and fantasy fiction are so popular, Donahue calls himself “an unrepentant realist.” His first novel, Madison House, is about the people who refused to move when the city of Seattle reshaped its downtown by leveling the steep hill near the waterfront, a project known as the Denny Regrade. Donahue was struck by photos of isolated houses perched atop miniature buttes, with all the surrounding land already excavated.

In an era where genre and fantasy fiction are so popular, Donahue calls himself “an unrepentant realist.” His first novel, Madison House, is about the people who refused to move when the city of Seattle reshaped its downtown by leveling the steep hill near the waterfront, a project known as the Denny Regrade. Donahue was struck by photos of isolated houses perched atop miniature buttes, with all the surrounding land already excavated.

“They were called spite mounds,” said Donahue. Donahue was intrigued by these people and by what the regrade meant for the once thriving, working-class neighborhood. “I couldn’t let it go.”

Madison House is based on one of these holdouts, a woman who ran a boarding house, which Donahue populated with a microcosm of neighborhood residents.

Madison House is based on one of these holdouts, a woman who ran a boarding house, which Donahue populated with a microcosm of neighborhood residents.

“What I like about historical fiction – at least the type I’m writing – is finding those gaps in the historical record. No one had written about the Denny Regrade. No one knew what was lost,” he said.

Donahue’s short-story collection, The Cornelius Arms, is based on the neighbors in his first apartment in downtown Seattle, at a time when you could still find a funky, rundown building with a great view of the Olympic Mountains. They were such characters that “there was not a lot of need to embellish,” he said.

His books also weave in autobiographical elements and real historic figures. His second novel, Clara and Merritt, is a ‘Romeo and Juliet’ tale about love between people from two powerful, feuding labor unions in Seattle during the Depression, the Teamsters and the Longshoremen. The characters are also loosely based on Donahue’s parents, a union arbitrator and an illustrator.

His books also weave in autobiographical elements and real historic figures. His second novel, Clara and Merritt, is a ‘Romeo and Juliet’ tale about love between people from two powerful, feuding labor unions in Seattle during the Depression, the Teamsters and the Longshoremen. The characters are also loosely based on Donahue’s parents, a union arbitrator and an illustrator.

Donahue’s career as a writer has always been combined with teaching, inspired by a formative experience in his own life. “It’s always been my thing, to write,” said Donahue. “It starts with Don Delo, my ninth-grade English teacher. He set my head on fire with literature and writing.”

Delo gave Donahue a notebook so he could keep a journal, a practice Donahue has continued – for 43 years. Delo also kept a wide variety of literature on a bookshelf in the classroom, where Donahue discovered Northwest writers like Ken Kesey and Tom Robbins.

In fact, all Donahue wanted to do was read. At 15, he dropped out of high school. “The school wasn’t doing it for me – it was too constrictive, too confining. I just wanted to read what I wanted to read – which was all good stuff,” he said.

After dropping out, he made his first visit to Seattle with a friend. “I remember sitting under the viaduct in the rain, watching the ferries come and go. The city spoke to me,” he said. Three years later, he filled his orange backpack and moved to Seattle.

Despite dropping out of high school, Donahue always wanted to go back to school. He studied literature and writing at Seattle Central Community College and then enrolled at the University of Washington, where he got encouragement for his fiction.

After graduation, he and his wife, Susan, moved to Virginia. Donahue got a master’s degree and began publishing short stories. He followed that up with a PhD in literature and creative writing. They ended up spending more than two decades in the Southeast, in Oklahoma, East Texas, and Alabama.

After graduation, he and his wife, Susan, moved to Virginia. Donahue got a master’s degree and began publishing short stories. He followed that up with a PhD in literature and creative writing. They ended up spending more than two decades in the Southeast, in Oklahoma, East Texas, and Alabama.

Although they weren’t Southerners, Donahue and his wife both thrived in Alabama. “It was a Southern odyssey, but I always wanted to come back to the Northwest,” he said. When a teaching job at Wenatchee Valley College in Omak opened up nine years ago, it was the right time for a move. “One reason I came here to teach is because community college saved me,” he said.

“Teaching goes hand in hand with writing,” said Donahue. It all comes back to Don Delo and the influence a teacher can have on someone’s life, he said. “It’s rewarding. People start to discover they can articulate stuff that really matters.”

Donahue admits that he’s never far from his students’ struggles. “The only difference is I’ve been doing it longer and have more tools,” he said.

Serendipity

Serendipity

Donahue’s stories are characterized by a commanding sense of place, even though he often writes them at some remove from the setting. While he was in the Southeast, most of his writing still looked towards the opposite corner of the country.

The idea for one of the stories in Three Sides Water was planted when Donahue was visiting Rialto Beach on the Olympic Peninsula with his students from Alabama. A forest ranger casually mentioned a magician and mentalist who lived on the beach. “It just blew my mind – I knew I had to find out about this guy,” said Donahue.

At Fort Worden in Port Townsend, Donahue stumbled across an unobtrusive plaque commemorating the period, from the late 1950s to early ’70s, when the fort served as a juvenile-detention center. Donahue tracked down an oral history of staff at the facility and even ran into a former inmate. It grew into a story about a young man who served time there, and who, like Donahue, found salvation in reading.

The third story in Three Sides Water grew out of Donahue’s interest in the old mill town of Shelton and in Bing Crosby, whose links to the Northwest have always fascinated him. The ideas converged in a character who moonlights as a Bing Crosby tribute singer.

Donahue conceived the book as a sort of trilogy representing the Olympic Peninsula. In fact, he saw the short novels that make up the book as peninsulas themselves – not really islands or mainland, and not entirely separate or attached.

The stories encompass three eras on the Peninsula – 1925, 1970, and 2015. “The more I worked with them as a group, the more they seemed to coalesce. The characters are all looking back, reckoning with something, coming to terms, finding accountability, asserting independence to move on with their lives. They’re coming-of-age stories,” he said.

“Once I start to immerse myself in the project, the process becomes very generative,” said Donahue. Donahue uses a working notebook to try out plot turns or have characters cross paths – and then to see where it leads.

“Sometimes it’s more like diary writing,” he said – a place to explore questions like “Why am I writing this? Who cares? Why do I care?”

Championing Northwest Writers

In addition to his own fiction, Donahue is committed to publicizing books – fiction, nonfiction memoirs, and poetry – by Northwest authors who have been eclipsed by history. “These writers recognized the intersection of landscape and history. They’re all about place, but also history –which combined is very formative in Northwest identity,” said Donahue.

“They’re writers no one remembers, but they’re damn good writers. I just feel their books need to be recognized,” said Donahue. He set about doing that, first in a series of articles for the journal of the Washington State Historical Society. He told the editors he was confident he could find three or four writers worthy of attention. Ultimately, he featured 55. “It was one of the best projects of my life – I just kept discovering stuff,” he said.

Donahue is now finishing a collection of his articles on of his best discoveries, with profiles of the writers, reappraisals of their books, and excerpts from those books. It has a tantalizing title adapted from one of the books – Salmon Eaters, Apple Knockers, Sagebrushers, and Rain Worshippers: Washington’s Lost Literary Legacy.

Donahue is also working on a collaboration with Robin Nelson Wicks, who taught art at Liberty Bell High School until last year. “Miscellaneous Friends” pairs Nelson Wicks’ portraits with Donahue’s written sketches of characters they invented independently – but that matched up seamlessly.

Several of the sketches have been published in the Los Angeles–based magazine Forth. Donahue and Nelson Wicks are working on 50 literary/art portraits for a book.

As he wraps up these projects, Donahue is looking towards his next novel. He’s nursing several ideas, including one about Okanogan County. “The county fascinates me – how big it is, how diverse it is. I imagine something that could capture this valley – with a historic but fantastical element,” he said.

As he wraps up these projects, Donahue is looking towards his next novel. He’s nursing several ideas, including one about Okanogan County. “The county fascinates me – how big it is, how diverse it is. I imagine something that could capture this valley – with a historic but fantastical element,” he said.

He’s also contemplating a novel based on the life of one of the Washington authors he’s profiled, an accomplished writer who was murdered by her second husband.

The stories could lead anywhere. “The more you write, the more ideas come to you – you never drain yourself,” he said.

Donahue is the author of The Cornelius Arms, a short story collection; the novels Madison House and Clara and Merritt; and Three Sides Water, a collection of short novels. He is the co-editor of Seven Years on the Pacific Slope, a memoir by Mrs. Hugh Fraser about her life in the Methow Valley in the early 20th century; and of two literary anthologies, Reading Portland: The City in Prose and Reading Seattle: The City in Prose. Excerpts of his work are on his website at www.peterdonahue.org.

CLICK HERE to download PDF of the Winter 2018-19 ART Magazine

Photographs were taken by Sol Gutierrez.