By Marcy Stamper

By Marcy Stamper

Photos by Sol Gutierrez

CLICK HERE FOR PDF OF SUMMER ART MAGAZINE

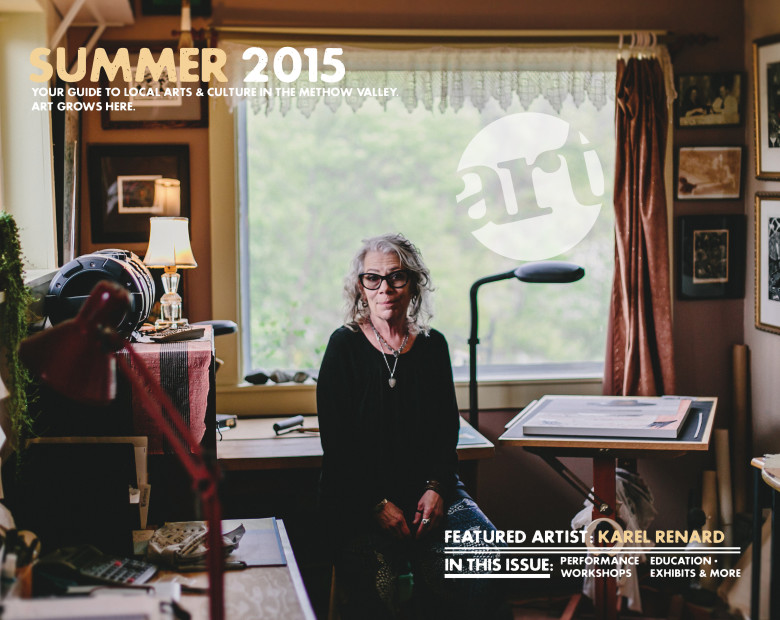

Karel Renard has always been an observer.

When she was a child, her family moved a lot, relocating to a new house or apartment virtually every year. Six decades later, Renard still vividly remembers each one. “I can describe every single house and room. I can draw the floor plan of my grandmother’s house right now,” she said.

“My memories are very sensory,” said Renard, “but they don’t come with sound, dialogue, script, or story.”

For an artist, not having a narrative direction is actually quite freeing. Renard, who specializes in printmaking, has a remarkable talent for figuring out how to translate the complicated image in her mind’s eye into carvings on wood or linoleum and then into a lush, textural print.

“I started seeing the world that way, with negative and positive spaces reversed, and the world in black and white,” said Renard. “It just became second nature.”

Renard has always been creative—she spent her childhood drawing and writing plays and poetry, and later studied apparel design—but she never thought of herself as an artist until she discovered printmaking two decades ago.

Growing up, Renard was surrounded by paintings and sculpture and music, particularly jazz. Her mother always supplied her with a big block of clay to play with. She remembers being an incredible daydreamer.

As a young adult during the 1960s, Renard made all kinds of art, but she always gave it away, or sometimes even threw it away. “I didn’t think of myself as an artist—it’s just what I did,” she said. “It’s just what people did—we made music and art.”

Later, when her children were young, she grabbed snippets of time to sketch, embroider, or write, although she still had no particular goal or artistic vision. “I was all over the place,” she said. “I made puppets, giant papier-mâché animals, did weaving, writing.”

It was perhaps serendipity when Renard’s husband, Jeffrey Winslow, a painter and multi-media artist, decided one year that he was too busy to carve their annual Christmas-card woodblock and urged Renard to do it instead.

“It really spoke to me,” Renard said. Printmaking combined drawing and imagery and was tactile. She loved the physicality of carving and the elemental black-and-white palette of the prints.

“Color was not my thing,” she said. “I dressed in black. Even when I was a kid, I did lots of pencil drawings.”

Printmaking proved completely absorbing. “I got really addicted—I didn’t want to do anything else,” she said. “For the first time in my life, I identified as an artist, as a printmaker. It was very fulfilling.”

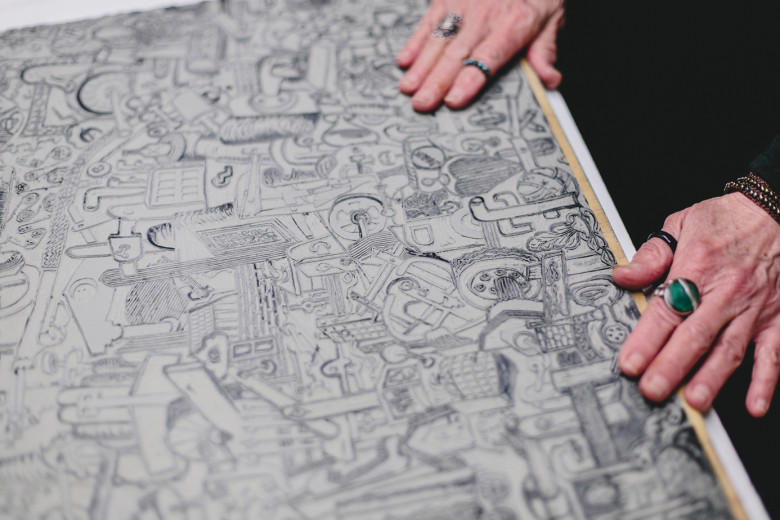

In her prints, all those sensory images Renard files away emerge in designs that are not exactly abstract—they contain recognizable elements like people and plants, and a fanciful menagerie of animals from dogs to sea creatures. But they are somewhat surreal, with human figures morphing into insects or appearing to turn inside out.

In one print, a bowl decorated with Chinese motifs overflows with buildings, all balanced on the back of a kneeling, winged human. In another print, butterflies grow roots. Human figures have intricate geometric patterns for their musculature. Music and dance become visual motifs.

“I know a little bit about where I’m going, but it changes along the way and always comes out differently from what I imagine,” said Renard. “But there is a starting point.”

Those starting points are varied. “It could be a piece of a puzzle or of an image,” she said. “It often will come to me in a visual sentence. It’s interesting—music and books and visual art—they all intertwine and feed each other—they’re not separate.”

In fact, Renard’s block prints—most just black-and-white, with no tonal gradations and only occasional swatches of color—seem like the perfect expression of the relationship between an inner consciousness and the world outside.

Her prints rely on a keen talent for balancing positive and negative space—the lines and shapes of a picture and the white space in between. In most art, you draw your subject directly—for a tree, you draw the trunk and the branches. But in block printing, you draw the space that surrounds the branches and the blank areas between the leaves.

“I started seeing the world that way, with negative and positive spaces reversed, and the world in black and white,” said Renard. “It just became second nature.”

Although self-taught as a printmaker, Renard formally studied fabric and apparel design. She learned to create custom hats and clothes, designed clothing patterns, and wove fabrics. But catering to people’s tastes in fashion was not for her. “Never take  something you do for fun and turn it into a job,” she said.

something you do for fun and turn it into a job,” she said.

Still, she enjoyed doing alterations and fixing antique garments. For a while, she worked for a chic French clothing boutique in Seattle where customers sipped champagne while she adjusted their new clothes. She also dressed models for fashion shows. “It was fun—it was like theatre,” she said.

In 1995, when she and Winslow moved to a house at the top of Texas Creek with no electricity or running water, Renard continued her artistic explorations in between pumping water and growing hundreds pounds of potatoes. “I sold tons of cloth things at Confluence Gallery, just trying to make some money,” she said. She made stuffed bean-bag angels as holiday ornaments, bags for leftover slivers of soap, and printed wood blocks on burlap.

But once she discovered printmaking, she sold all her sewing machines and fabric and started collecting paper instead. In addition to printing, the paper goes into collaged cards, which Renard started making for her children and grandchildren. “They’re just silly and fun—just cut paper and color. But it’s not my soul,” she said.

The cards are light-hearted and whimsical, but by no means simple. There are masked insects, a person walking a lizard on a leash, and everyday scenes of gardening and relaxing. Some are personal or about her family, and some are just eccentric images. “I’m just wacko,” said Renard. “I don’t know where that chicken-lady came from.”

The prints are in a different category, intellectually, conceptually, and physically demanding. “My prints are serious—I work hard on my prints,” said Renard.

When she first started printmaking, Renard carved her complex designs into wood blocks. Although she loved the effect and texture of the grain, she ultimately switched to linoleum, which is easier on her hands and allows greater design flexibility.

For 10 years Renard also printed every piece by hand, laboriously rubbing each sheet of paper over the carved block to transfer the image. It was hard to make even a single satisfactory print, let alone a series of 25, and she was wasting countless sheets of paper. She finally stopped by the Methow Print Arts studio in Twisp and got a lesson on using their professional printing press.

For 10 years Renard also printed every piece by hand, laboriously rubbing each sheet of paper over the carved block to transfer the image. It was hard to make even a single satisfactory print, let alone a series of 25, and she was wasting countless sheets of paper. She finally stopped by the Methow Print Arts studio in Twisp and got a lesson on using their professional printing press.

“I ran a print and pulled it out. I just started weeping, it was so perfect, so beautiful, so easy. I never rubbed another print,” she said. After Methow Print Arts closed, Renard invested in her own press, a solid-steel marvel that is still the most expensive thing she’s ever bought.

A personal highlight of her career was being included in “Beyond the Surface,” an exhibit of three print artists at Confluence Gallery in 2012. The exhibit featured an evolution of her block prints created over three years.

“Initially, I wanted stuff with meat, worldly subjects that affected my life, like the justice system or water—people’s absurd notion that water is going to be there forever,” said Renard. She created prints about trees, about balance, and personal images about her childhood and about raising babies. One of her favorites shows a large egg splitting in two and surrounded by flames.

She’ll throw paper on the floor and do big, gestural chalk drawings to loosen up. “I have to rule everything out,” she said. “If I start contemplating all the great artists, I would just go to bed and read a book. Then I ask why I’m doing the dishes, or baking a cake—why am I putting off the thing I love the most?”

In addition to the cards, Renard pursues other, more-casual projects that provide a diversion from the rigors of printmaking. For the inaugural exhibit in the Spartan Art Gallery at TwispWorks, she made a series of insect drawings and collages of what she calls “strange metamorphosis.”

She reserves printmaking f or her most personal explorations. “I don’t want to have to create a huge body of work in order to be taken seriously. I don’t want to have to be focused like that—I want to be able to change,” she said.

or her most personal explorations. “I don’t want to have to create a huge body of work in order to be taken seriously. I don’t want to have to be focused like that—I want to be able to change,” she said.

And, despite the satisfaction she derives from carving a piece of linoleum, it still doesn’t come easily. “Every beginning’s a beginning. It never gets better,” said Renard. “You already have self-doubt to take a blank piece of paper or canvas and make something—it’s crippling, like getting to the highest peak.”

She’ll throw paper on the floor and do big, gestural chalk drawings to loosen up. “I have to rule everything out,” she said. “If I start contemplating all the great artists, I would just go to bed and read a book. Then I ask why I’m doing the dishes, or baking a cake—why am I putting off the thing I love the most?”

She has learned to stay with the process. “It’s just the beginning—if I get through the door, I know I’m going to be very happy. The work starts to come together and to take over.

“Once you start, it’s mesmerizing—you just get to have fun. It’s flowing—that’s where the addiction comes in,” she said.

Renard’s exhibit of original cards is at Cinnamon Twisp Bakery in Twisp through August 1. Her printed cards are always available there. Visit her artist page @ www.methowarts.org/artists/karel-renard/for updates.

- Read the full Summer ART Issue CLICK HERE FOR A PDF

- Sign Up for our newsletter.