FALL ART MAGAZINE: click here for PDF.

By Marcy Stamper. Photographs by Sol Gutierrez.

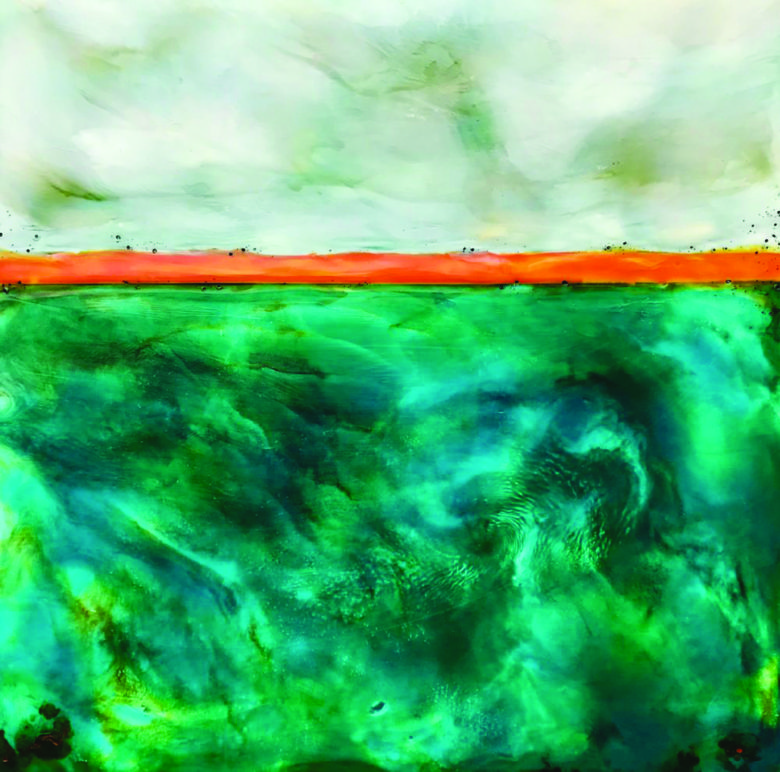

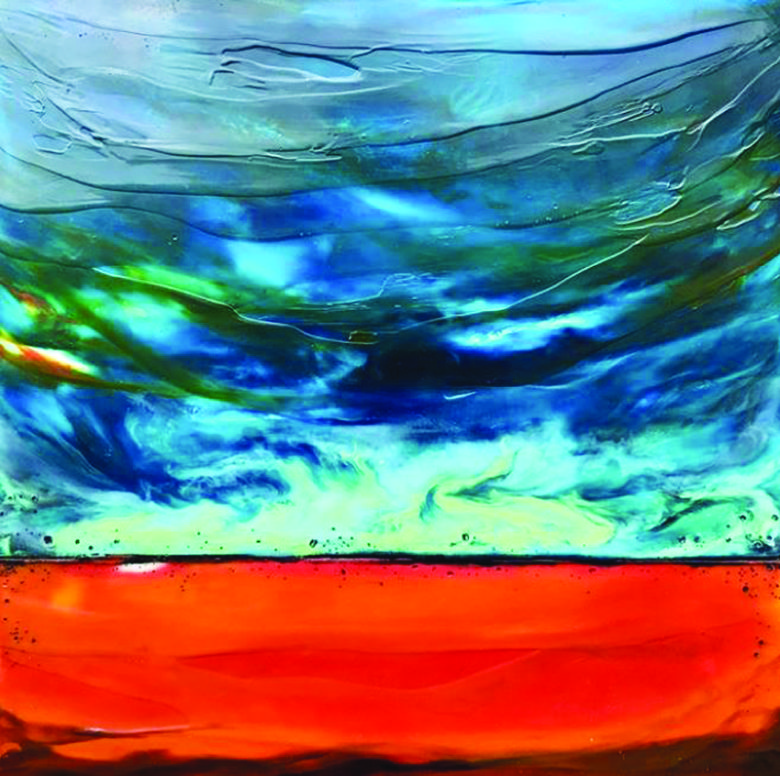

Tamera Abaté finds endless potential in a horizon. “I’m pretty fascinated with ridgelines and horizon lines,” she said.

Abaté explores that fascination in abstract encaustic paintings, which feature wide, horizontal bands of luminescent color done in melted wax.

Abaté explores that fascination in abstract encaustic paintings, which feature wide, horizontal bands of luminescent color done in melted wax.

Abaté knows those landscapes intimately – she grew up on a wheat farm near Moses Lake and has also lived on the ocean. “There were huge horizon lines – they weren’t chopped up by mountains like in the Methow,” she said. “I thought I could practically see the curvature of the earth, it’s such a long line. What’s behind it seems like the edge of something.”

While the horizontal fields of aqua, ivory, and rust in a painting may suggest an ocean landscape in the sunset, or wheat fields beneath wispy clouds, the paintings aren’t meant to represent anything that precise. Abaté’s work is abstract, more about motion and her mood than any specific place or subject.

“Someone in the Winthrop Gallery said he got lost in my painting,” Abaté said. “That’s the perfect compliment – that’s what it’s supposed to do.” It’s the open-ended effect she’d to have on everyone. “What do those colors mean to you?” she said.

While she has always been driven to make art – and has sold everything from rhinestone-studded T-shirts to pottery – Abaté has had little formal art education. “I always need to do something with my hands. I was raised that way – working on the farm was a very physical childhood,” she said.

Abaté’s family was artistic, but the demanding farm schedule left little time for art making. Her grandmother was a talented oil painter of landscapes and her mother sewed and dabbled in art when she had the chance.

As a kid, Abaté collected pens, markers, and paper, which she preserved in a special box. “Sewing was the most art-related thing I did as a kid,” she said.

When her children were young, Abaté would squeeze in time for creativity whenever possible. She painted watercolors while her kids napped, keeping the paintings small so she’d have the satisfaction of finishing, she said.

She also did more elaborate projects, including a series of handmade books, quirky and captivating multi-media creations that unfold into glorious accordions of words and color. Abaté painted the pages and collaged souvenirs from her daily life or travels, and then hand-lettered accounts of their activities.

“Those books would be the first thing I’d take if there was a fire – they’re irreplaceable stories of family experiences,” Abaté said.

“Those books would be the first thing I’d take if there was a fire – they’re irreplaceable stories of family experiences,” Abaté said.

In fact, the handmade books are what led Abaté to encaustics. After she showed her brother a book containing pages she’d covered with melted beeswax, he said it reminded him of encaustics. Abaté looked up the unfamiliar term.

Soon she’d checked out all the library books she could find on encaustics. She taught herself to paint with wax, experimenting with small pictures of birds and abstract color studies. She was hooked. “It’s swept me away the last five years,” she said.

“The cool thing is that it’s pretty environmentally friendly. It’s just beeswax and tree resin, with some pigment. There’s not a lot of waste,” Abaté said.

While rich with saturated color, the wax is translucent enough to reveal complex layers of texture and pattern. Abaté uses a pancake griddle, a warming plate, a tacking iron, and different-sized propane torches – including a tiny one used to caramelize sugar on crème brulée.

The wax can be reused. When Abaté scrapes wax off a painting to expose the layer below, she gathers the curls and shavings to be melted down again. A small forest of colorful stalagmites is growing next to the warming tray where she keeps pots of molten wax. “It’s like a gnome family under there,” she said. Those little gnomes also go back in the pot.

Abaté starts a new painting by applying two layers of clear melted wax with a brush. Because the wax dries right away, she melts it with an iron to spread it around the board, smoothing some areas and leaving subtle ridges elsewhere. The ridges show through the subsequent layers of pigmented wax, affecting the color density and adding pattern and texture. Every layer has to be fused to the one beneath it with heat.

Abaté starts a new painting by applying two layers of clear melted wax with a brush. Because the wax dries right away, she melts it with an iron to spread it around the board, smoothing some areas and leaving subtle ridges elsewhere. The ridges show through the subsequent layers of pigmented wax, affecting the color density and adding pattern and texture. Every layer has to be fused to the one beneath it with heat.

“One of the things I really like about encaustics is that there’s no other medium with such luminosity and depth,” Abaté said. Since the pigment is suspended in clear wax, you can see through each layer, and the final surface glistens. Most paintings get at least 10 layers before they’re done.

When Abaté applies base layers of clear wax, she could try to create a design by building up ridges in certain areas. “But that would take the fun out. The high points are like surprises” in the final painting, she said.

Abaté pushes the pigmented wax around on the board with a large propane torch, but there’s a limit to how much control she has. “It has a little bit of a mind of its own,” she said. “What happens happens, but I can’t re-create it.” Then she carefully scrapes away layers of wax to reveal colors and textures below.

Abaté pushes the pigmented wax around on the board with a large propane torch, but there’s a limit to how much control she has. “It has a little bit of a mind of its own,” she said. “What happens happens, but I can’t re-create it.” Then she carefully scrapes away layers of wax to reveal colors and textures below.

The layered process leaves hints of color – in tiny flecks, amoebic blotches, and swirling patterns – in an abstract arrangement. Billowy white areas in an azure field suggest clouds; more angular forms look like birds in flight or sea creatures. Look again and they recall crop patterns seen from an airplane, whitecaps on the water, or a basic study of color and hue.

The layered process leaves hints of color – in tiny flecks, amoebic blotches, and swirling patterns – in an abstract arrangement. Billowy white areas in an azure field suggest clouds; more angular forms look like birds in flight or sea creatures. Look again and they recall crop patterns seen from an airplane, whitecaps on the water, or a basic study of color and hue.

“I like how meditative and physical it is, particularly on a big piece,” Abaté said. Because the wax cools so quickly, she has to work fast. “I love watching it go back and forth from dark to light or light to dark, and how the multiple layers interact,” she said.

When she starts a new painting, Abaté has a color scheme in mind – but not a particular place. “Paintings that are more suggestive of landscapes do fit in some degree of realness – for example, the horizon line – even though you would never see that cross-section of earth, horizon, water, and sky,” she said.

When she starts a new painting, Abaté has a color scheme in mind – but not a particular place. “Paintings that are more suggestive of landscapes do fit in some degree of realness – for example, the horizon line – even though you would never see that cross-section of earth, horizon, water, and sky,” she said.

She realizes that some people still crave a recognizable subject. “When a person looks at abstract art, their brain becomes uncomfortable because they can’t identify or categorize it,” she said. “It’s human nature to categorize what we see.”

But many viewers respond to the atmosphere she creates of colors, energy, and motion.

It’s common for artists take photos or sketches as reference material, but Abaté has honed her ability to remember the way she feels. “When I’m out in nature – at the beach or in the mountains – I’m always observing the whole landscape, and noticing what emotions arise. Rather than taking a photo, I try to memorize that feeling in my mind, and try to transfer it into a painting,” she said.

Abaté does some representational paintings – primarily small paintings of birds and horses that help her experiment with new encaustic techniques. The vividly colored birds aren’t meant to be scientifically accurate – they’re playful versions of chickadees, hummingbirds, and exotic tropical birds.

Abaté does some representational paintings – primarily small paintings of birds and horses that help her experiment with new encaustic techniques. The vividly colored birds aren’t meant to be scientifically accurate – they’re playful versions of chickadees, hummingbirds, and exotic tropical birds.

Before she became hooked on encaustics, Abaté worked mostly in ceramics. She made mugs and plates decorated with dancing birds and flowers. They were uplifting, with inspiring and humorous sayings. “It was fun to watch people. The mugs made them smile,” she said.

She also sculpted ceramic Leaf Spirits – whimsical creatures that were part human and part flower or vegetable, often with an interior void for candles.

But in encaustics, Abaté has found a way to express her experience of nature. “I simply notice things. It’s like slow motion, like how the light comes through the trees and the shades of green change as I walk under the tree.”

But in encaustics, Abaté has found a way to express her experience of nature. “I simply notice things. It’s like slow motion, like how the light comes through the trees and the shades of green change as I walk under the tree.”

“This has been a good path. I really enjoy where it’s taking me. I’m passionate about it,” she said.

It’s also a business. “It just so happens I love doing it,” she said.

FALL ART MAGAZINE: click here for PDF.

Photographs were taken by Sol Gutierrez.

Photographs were taken by Sol Gutierrez.