Lynn Shelton: director, writer, editor, daughter

Summer 2020

by Ashley Lodato

Methow Arts staff writer

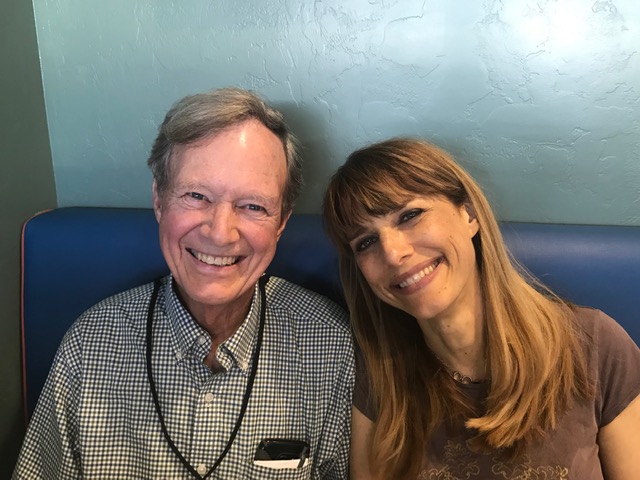

When director, editor, writer, and actor, Lynn Shelton died May 16, 2020 at the age of 54, the world lost a dynamic member of the arts community and Twisp River residents Mac Shelton and Frauke Rynd lost a beloved daughter.

A graduate of the University of Washington’s School of Drama, Shelton moved to New York City to act and then to study photography and teach videography at the School of Visual Arts before settling in Seattle, where she made films and raised her son, Milo.

Shelton leaves behind an impressive body of work that includes feature films like Humpday (2009), Your Sister’s Sister (2011), Outside In (2017), the TV mini-series Little Fires Everywhere (2020), and dozens of other film and TV projects. But even more importantly, Shelton leaves behind a legacy of, as one colleague put it, “directing and living her life as a deep and pure enthusiast for people’s best potential.”

Shelton’s father, Mac, says, “From an early age Lynn showed an artistic bent. She was always drawing and writing, always singing and dancing, always acting.” As a child, Shelton was involved in what is now Seattle Children’s Theatre. Shelton sang in school choirs and acted in school plays. As a teenager she spent a summer as a cast member in the musical “Free to Be You and Me,” touring western Washington. She took art classes through the University of Washington and danced from preschool through sixth grade.

Shelton had a passion for music and the importance it plays in people’s lives. Her mother, Wendy Roedell, sings in a medieval women’s choir in Seattle, and Shelton sang in the renowned Northwest Chamber Chorus in the early 2000s. The year Shelton graduated from high school, Roedell’s choir had a concert scheduled for the same night as Shelton’s commencement ceremony. “Mom,” Shelton said, “you doing this concert is more important than seeing me graduate.” After her graduation ceremony ended, Shelton hustled over to the concert hall to catch the end of her mother’s concert.

Shelton’s “tastes and skills were eclectic,” her father says. “Medieval, Gilbert & Sullivan, Broad-way musicals. For a 50th birthday party in 2015 she rented a former church (the Fremont Abbey, now a popular performance venue in Seattle) and invited musicians to perform. She sang duets with them, including with one of her favorite Seattle-based groups, The Moondoggies.”

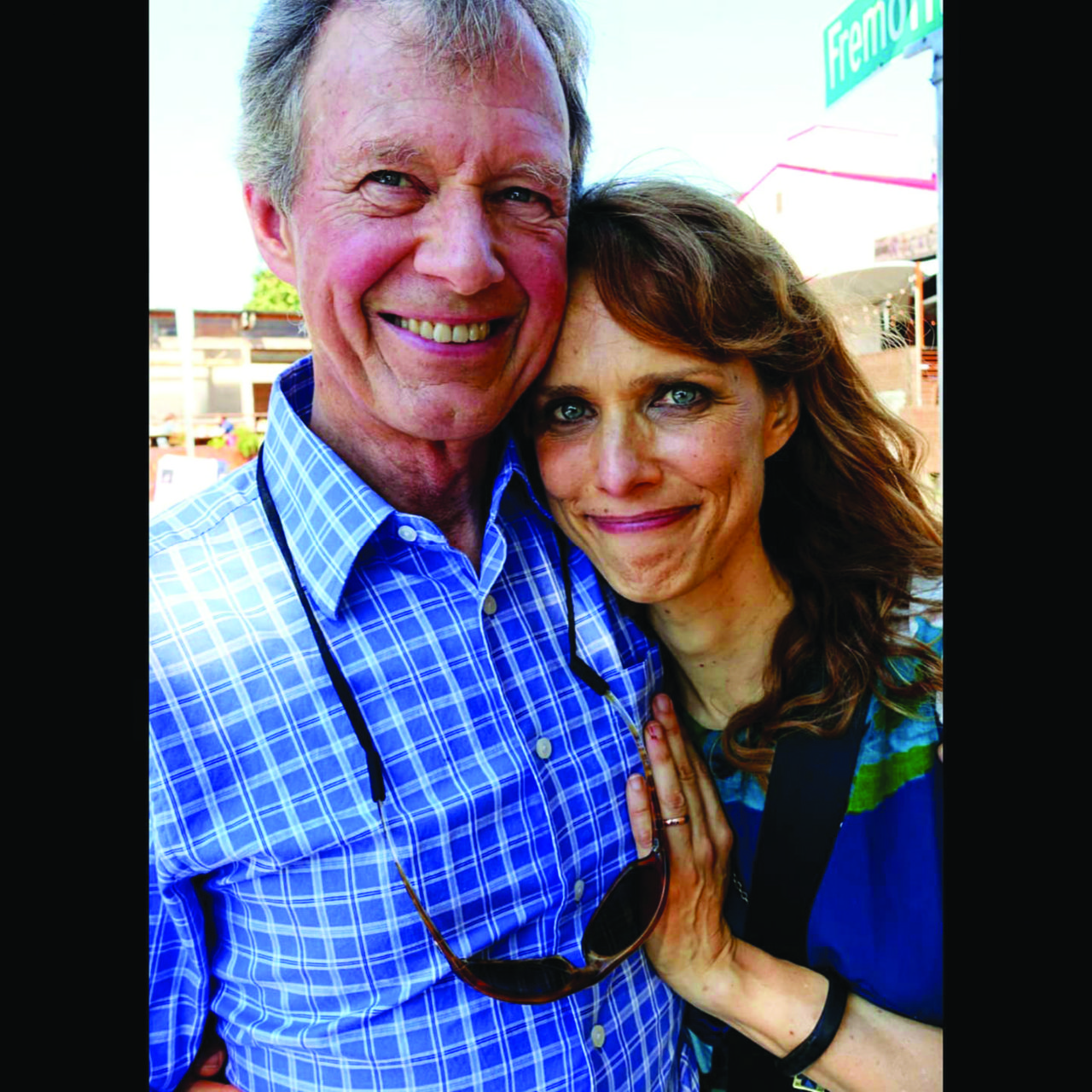

Shelton’s understanding of people’s aspirations and how to nurture them was legendary. Says Rynd, (who Shelton called her “other mother” from the age of 16 on), Shelton “was always focused on others’ artistic endeavors and helping them achieve their goals. She connected friends and acquaintances with those who could help them. She was always encouraging others, elevating them.”

Shelton’s father says, “Lynn had a way of making people feel affirmed and validated,” a sentiment that was echoed by actor Rosemarie DeWitt, with whom Shelton collaborated on the films My Sister’s Sister and Touchy Feely (2013). “To work with Lynn was to be known and seen and cherished and valued for yourself,” DeWitt said in a tribute to Shelton.

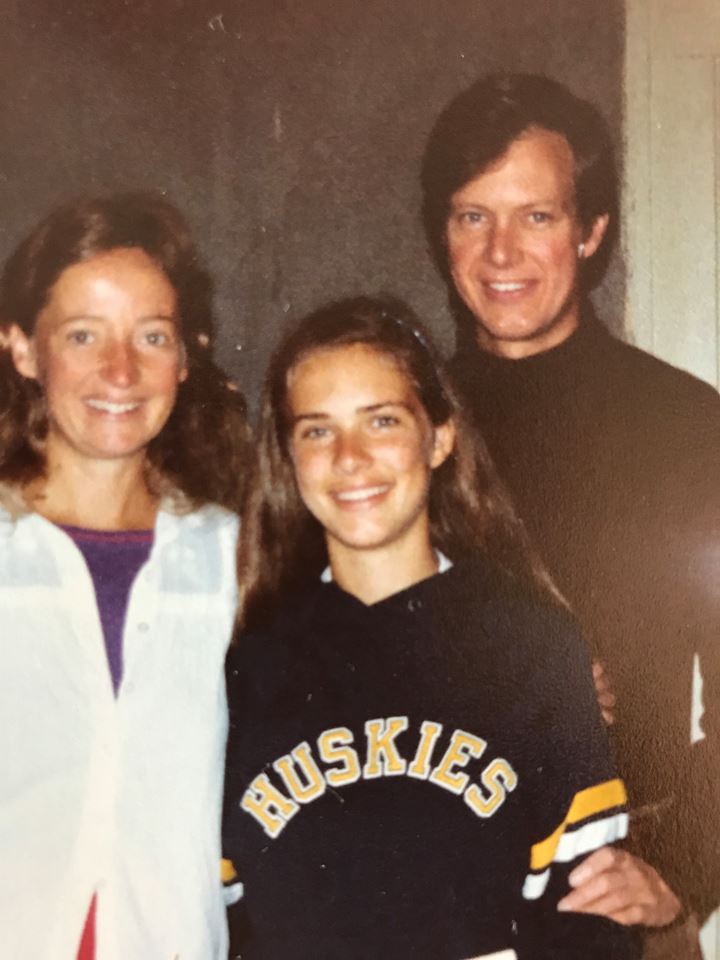

Shelton’s connection to the Methow Valley began on Mac Shelton and Rynd’s honeymoon in the 1982. “After we got married,” Rynd says, “we piled our collective four kids into a classic red and white VW bus and spent two weeks camping and backpacking. For the last night of the honeymoon we all backpacked to Windy Pass to spend the night in the Pasayten Wilderness.” Mac Shelton says, “On the second to the last night it was raining, so we stayed at the Idle-a-While motel in Twisp.” Rynd adds, “We got two rooms that night.”

Rynd and Mac Shelton bought property up the Twisp River in 1991, and since then have hosted 15 “Camp Twisp” seasons with their five grandchildren, including Milo, who is now 21. “Milo has spent a lot of time over here,” says Mac Shelton, “and Lynn was able to write some of her scripts here.” Shelton also filmed her 2008 film, My Effortless Brilliance, on Rynd and Mac Shelton’s property.

Shelton was known for her collaborative style of directing, which invited cast and crew members into the creative process. “She’d start with an idea and then find a group of people to help her work toward that idea,” Mac Shelton says. “She always valued their input, recognized that they were humans who got tired, who had bad days, and questions. She tried to get people home to their families each night, to rejuvenate.”

Mac Shelton adds, “Joshua Leonard [who co-starred in Humpday], said that when he first showed up on the set, he thought, ‘This is never going to work—she’s too nice.’” But it worked, spectacularly, thanks to Shelton’s empowering style. Shelton was “kind and collaborative,” Mac Shelton says. “She directed in a way that elevated everyone.”

Always working on a tight budget, Shelton was decisive out of necessity. Mac Shelton attributes some of this decisiveness to her experience as a writer and particularly as an editor. “Editing a film gives you a chance to rewrite it,” Mac Shelton says. “There’s so much you have to cut out before you get to the gold.”

Shelton learned to edit on the job, “crafting microbudget, dialogue-driven, semi-improvised features on digital video,” writes Jason Bailey in Shelton’s New York Times obituary. Shelton was already interested in filmmaking when she moved to New York, but says she did not have the confidence to make a movie.

But after attending a 2003 talk by the French filmmaker Claire Denis, Shelton had an epiphany. “Oh my God,” Shelton thought. “She was 40 when she made her first film. I thought it was too late for me.” Shelton realized, “Oh, I still have three more years.” She released her first feature film, We Go Way Back, in 2006, and just three years later Humpday put her on the indie film map, winning a prize at the Sundance Film Festival in 2009.

Shelton addresses We Go Way Back and its autobiographical components for Shelton. “Lynn always talked about the ‘geisha years’ for girls. When you’re a pre-teen girl, you feel like you can do anything. You’re powerful, you’re young, you’re emerging. And then you get aware of men, and the world, and how people see women, and you lose your power. You become submissive, you become what the world wants you to become.”

But later, Rynd says, “You come back into that power. In your 40s, as a woman, that’s when you get that confidence back. Before that you think, ‘I can’t do this,’ or ‘I’m not good enough.’ And that’s when Lynn starting making her award-winning films, in her 40s. She had this strong feminist trait that she had to grow into.

As a mother, “Lynn was so devoted,” Mac Shelton says. “After Milo became deaf [due to contracting meningitis], Lynn and Kevin [Seal, Milo’s father] jumped into learning sign language, to make sure he was able to lead a full life.” Mac Shelton says that as soon as Milo was born, Shelton put him on a wait list at a Seattle daycare. When they called her to tell her there was space for Milo, Shelton had to tell them that Milo was deaf. “So some of the daycare workers learned sign language,” Mac Shelton says. He and Rynd learned to sign as well.

Milo attended the Northwest School for Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Children, where he learned to sign with Signing Exact English (SEE) and later with American Sign Language (ASL). To honor Shelton and support the services that were instrumental to Milo’s success, Shelton’s two sets of parents have established the Shelton/Seal Family Fund at the school that will “ensure that, like Milo, children for generations to come will have the opportunity to thrive.”

Shelton lived with emotion and her films reflect this. “She was so full of laughter and joy,” Rynd says. “She had an exuberance for life, and wasn’t afraid of change.”

Genevieve Cole, co-owner of Winthrop’s Barnyard Cinema, says, “[Shelton] captures the emotional moments in life, the existential dread and private despair all of us experience yet seldom acknowledge in our practical and daily march toward illusive well-adjustedness (whatever that means). ‘It’s hard to find the cracks in happy people.’ Shelton finds them, and with such a light and adept touch, they sink deep and lend solace.”

Shelton’s father says, “I’m proud of her accomplishments, but I’m even prouder of her humanity.” Shelton’s films captured “regular people facing irregular or extraordinary scenarios that forced them to view their lives differently,” writes New York Times editor Mekado Murphy. Shelton’s compassion for other people, for those on the margins, those struggling—her humanity—allowed her to, in her own words, “take ideas that seem on paper to be ridiculous and make them emotionally real and plausible.”

“Shelton gives us a window, but fights the compulsion to tidy and summarize,” writes Cole. “She understands stories are snapshots, not conclusions. Her films end without resolve, just like life.”