Dan Nanamkin: preserving Indigenous culture

Spring 2021

by Ashley Lodato

Methow Arts staff writer

Storyteller, dancer, teacher, musician, author, and activist Dan Nanamkin is a member of the Chief Joseph Band of Wallaowa, Nez Perce, and Colville Confederated Tribes. Nanamkin, whose Native name means “Thunder and Lightning,” has been an advocate for Indigenous cultural arts since the 1900s, particularly in the area of youth engagement.

Nanamkin is committed to the preservation of Indigenous culture and sees himself as a bridge between modern ways and the traditions of the Syilx, the First Nations people of the Okanagan. His three-times great-grandmother, whose Native name was Mourning Dove, was an author and storyteller, recounting coyote legends. Nanamkin says his mother used to read Mourning Dove’s stories to him when he was a young boy, which sparked his passion for sharing the stories. “Storytelling is integral to indigenous culture,” he says. “It’s important for our people to understand the discipline, to value the oral tradition, to participate in the ceremonies that pass this information from generation to generation.”

Indigenous people are widely misunderstood, Nanamkin continues. “People know very little of us, and what they know comes from movies and TV, it’s very stereotypical. They learn nothing about how we honor the environment—the plants and the animals. They don’t learn our value system.”

To combat pervasive misunderstanding and stereotyping, Nanamkin has dedicated himself to traveling the nation as a speaker, performer, and educator, inspiring youth to learn about Indigenous cultures. He’s worked in Washington, California, Hawaii, and other states and Canadian provinces to build strength and community around culture, as well as to develop healthy lifestyles.

Indigenous culture is not represented with advocacy, Nanamkin says, which is why having the support of arts organizations like Methow Arts and grant funders is so critical to the promotion of Indigenous culture. Nanamkin notes that creating awareness is paramount to the elevation of Indigenous culture, and arts organizations can create awareness and publicity in a way that an individual can’t—particularly one who is so industriously traveling the continent (typically with minimal compensation), developing new programs, preparing TED talks, serving as an extra on movie sets, and tackling unique projects, such as his sovereignty camp.

Supported by Seattle’s Na’ah Illahee Fund and Potlatch Fund, Nanamkin started his Youth Warrior Camp in 2018, as a way to integrate youth into the traditional ways of life of the Sylix. The Youth Warrior Camp takes place on Nanamkin’s one-acre property in Nespelem, and is aimed at creating a traditional Indigenous village. Nanamkin was inspired by the half a year he spent at Standing Rock, from 2016-2017, when area youth from Indigenous communities organized to protest a proposed pipeline that would threaten the region’s drinking water and agricultural water supply, as well as ancient burial grounds and historic cultural sites.

“At Standing Rock I saw all these youth growing food and creating traditional structures,” says Nanamkin. “They were empowered by self-sufficiency. It was the first step to sovereignty.”

At his Nespelem property, Nanamkin, assisted by others who possess traditional skills, has taught young people in the Youth Warrior Camp to erect tipis and build a sweat lodge. They’ve planted a garden in what Nanamkin calls “my one acre of heavy duty clay.” They’ve established areas for frying and smoking meat, for pit cooking, and they’re working on building a pit house for storytelling, gatherings, and rites of passage.

“The odds are against me,” says Nanamkin, “because I’m not a gardener and I don’t know how to do all of these traditional skills.” But Nanamkin has cultivated a community of people who are enthusiastic about helping him. Members of the Indigenous community, tribal elders, and non-Native artists and makers visit the camp to work and exchange knowledge.

“It’s a big collaboration,” Nanamkin continues, “and it also combines modern with traditional. We’re doing permaculture and teaching beadwork, but we’re also learning about clean energy sources.”

One camp instructor brought goats the first year. “Now all the kids ask me, ‘where’s the goat guy?!’” Nanamkin says. “Somehow we have to develop more communication across cultures,” he says. “The kids are showing the way for the adults. The youth are going to make the changes because they thirst for this knowledge.”

The global pandemic forced Nanamkin to cancel the spring 2020 Youth Warrior Camp, but he is hoping to revive the camp in October. He’s committed, he says, “to serving youth and creating awareness of Indigenous culture.”

“Growing up on the reservation,” Nanamkin adds, “I know these barriers exist. We have to create this bridge. We have to learn how to create this unity in humanity. We need to pull in our brothers and sisters, and create a communication network.”

Nanamkin sees the arts as a way to create enthusiasm for traditional ways: crafts, music, beadwork, dancing, music, and wildcrafting. “Our Indigenous education is mind, body, and spirit,” he says. “We are losing our deeper rootedness, our spiritual education. Our stories and music have this spiritual foundation; Indigenous art is the language of the spirit.”

Society at large, Nanamkin repeats, “has no experience of the Indigenous spiritual importance. We’re invisible to so many people. To others, we’re just stereotypes. We need people to know that we are more than just Thanksgiving Day.”

To bring more authenticity to some of the biggest purveyors of dismissive racial stereotypes, Nanamkin has served as an advisor on and acted in modern films such as “Orphan Train.” He has also played small roles in other films featuring Indigenous people, such as the Netflix creation “Awake,” as well as numerous documentaries; he also recently received a call from a producer at the History Channel. Nanamkin is one of the faces of Standing Rock, appearing in dozens of press pieces about the Water Protectors protests of the Dakota Access Pipeline, including a Rolling Stone article about the recent court decision to shut down the pipeline, pending environmental review.

To revive the Indigenous movement, Nanamkin is also in the process of writing several books, and is scheduled to do a TEDx Talk in Spokane in the fall. He’s working tirelessly to spread awareness of Indigenous culture, although, admittedly, it can be exhausting, he says. “When I left Standing Rock I put my life and trust in the Creator’s hands,” Nanamkin says. “I’m going to continue to go forward doing what the Creator is telling me to do.”

In spite of, or perhaps because of, his experience on both sides of law enforcement, Nanamkin insists that “respectful exchange” is the only possible positive path forward. He has begun working on a cultural sensitivity training, in order to “step into the community level” with his ideas. As a an educator, he says, “it will be great to have a platform to speak to the police.”

Nanamkin also notes, “I also want to talk to workplaces, colleges, and communities and forge a relationship between my tribe and our traditional homelands and the people who reside there.”

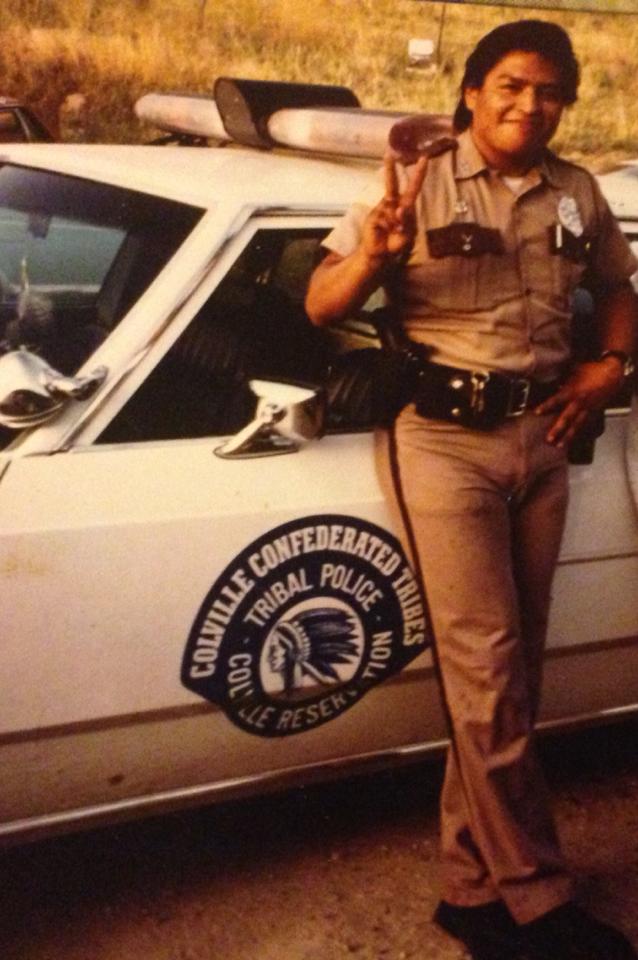

Prior to dedicating his life to creating awareness of traditional culture, Nanamkin served as a tribal police officer, after graduating from the Washington State Police Academy in Spokane. Nanamkin says that seeing others around him suffering from abuse and violence inspired him to enter law enforcement, but was discouraged by racism within the system. “I’ve experienced it myself,” Nanamkin says. “At Standing Rock we were abused and violated. And the media didn’t cover the full extent of the abuse.”

With the grants he has received recently, Nanamkin has plans to buy technical equipment like a looping machine and a video camera, to enhance his work at festivals and on music stages. “Music is a way to reach people,” he says. “I want to educate and entertain, to use music’s powerful platform to touch more people.”

Nanamkin’s work and influence are likely to endure beyond his tenure on the planet. “Even after my days on this earth have passed, I want the education to remain for the kids,” he says, “I’m a bridge—I was raised by the old timers and now I’m working with youth. How do we move forward together? There are a lot of people looking for answers about that. There are a lot of answers right here in this camp.”

Dan is a teaching artist with Methow Arts’ Artist-in-Residence program as a cultural resource, helping students, parents, and teachers learn more about Indigenous cultures. Access some of his recorded talks at the links below.

Learn more about Dan Nanamkin at his website.